Extracellular matrix

Plant cell walls

The extracellular matrix and cell wall

Introduction

We’ve spent a lot of time looking at what’s inside a cell. What, then, is on the outside? It depends a lot on what kind of cell you’re looking at.

Plants and fungi have a tough cell wall for protection and support, while animal cells can secrete materials into their surroundings to form a meshwork of macromolecules called the extracellular matrix. Here, we’ll look in more detail at these external structures and the roles they play in different cell types.

Extracellular matrix of animal cells

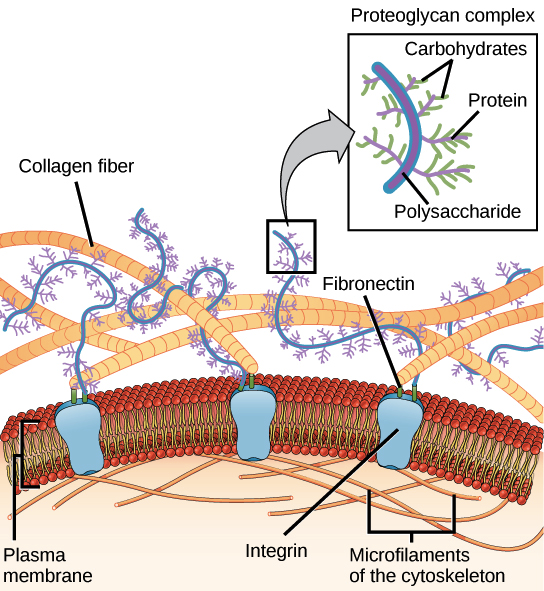

Most animal cells release materials into the extracellular space, creating a complex meshwork of proteins and carbohydrates called the extracellular matrix (ECM). A major component of the extracellular matrix is the protein collagen. Collagen proteins are modified with carbohydrates, and once they're released from the cell, they assemble into long fibers called collagen fibrils\[^{1}\].

Collagen plays a key role in giving tissues strength and structural integrity. Human genetic disorders that affect collagen, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, result in fragile tissues that stretch and tear too easily\[^2\].

In the extracellular matrix, collagen fibers are interwoven with a class of carbohydrate-bearing proteoglycans, which may be attached to a long polysaccharide backbone as shown in the picture below. The extracellular matrix also contains many other types of proteins and carbohydrates.

Image credit: OpenStax Biology.

The extracellular matrix is directly connected to the cells it surrounds. Some of the key connectors are proteins called integrins, which are embedded in the plasma membrane. Proteins in the extracellular matrix, like the fibronectin molecules shown in green in the diagram above, can act as bridges between integrins and other extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen. On the inner side of the membrane, the integrins are linked to the cytoskeleton.

Integrins anchor the cell to the extracellular matrix. In addition, they help it sense its environment. They can detect both chemical and mechanical cues from the extracellular matrix and trigger signaling pathways in response\[^{4,5}\].

Blood clotting provides another example of communication between cells and the extracellular matrix. When the cells lining a blood vessel are damaged, they display a protein receptor called tissue factor. When tissue factor binds to a molecule present in the extracellular matrix, it triggers a range of responses that reduce blood loss. For instance, it causes platelets to stick to the wall of the damaged blood vessel and stimulates them to produce clotting factors.

The cell wall

Though plants don't make collagen, they have their own type of supportive extracellular structure: the cell wall. The cell wall is a rigid covering that surrounds the cell, protecting it and giving it support and shape. Have you ever noticed that when you bite into a raw vegetable, like celery, it crunches? A big part of that crunch is the rigidity of celery’s cell walls.

Fungi also have cell walls, as do some protists (a group of mostly unicellular eukaryotes) and most prokaryotes—though I don't recommend biting into any of those to see if they crunch!

Like the animal extracellular matrix, the plant cell wall is made up of molecules secreted by the cell. The major organic molecule of the plant cell wall is cellulose, a polysaccharide composed of glucose units. Cellulose assembles into fibers called microfibrils, as shown in the diagram below.

Image credit: "Plant cell wall diagram" by Mariana Ruiz Villareal, public domain

Most plant cell walls contain a variety of different polysaccharides and proteins. In addition to cellulose, other polysaccharides commonly found in the plant cell wall include hemicellulose and pectin, shown in the diagram above. The middle lamella, shown along the top of the diagram, is a sticky layer that helps hold the cell walls of adjacent plant cells together\[^{6,7}\].

Cell-cell junctions

Introduction

If you were building a building, what kinds of connections might you want to put between the rooms? In some cases, you’d want people to be able to walk from one room to another, in which case you’d put in a door. In other cases, you’d want to hold two adjacent walls firmly together, in which case you might put in some strong bolts. And in still other cases, you might need to ensure that the walls were sealed very tightly together – for instance, to prevent water from dripping between them.

As it turns out, cells face the same questions when they’re arranged in a tissue next to other cells. Should they put in doors that connect them directly to their neighbors? Do they need to spot-weld themselves to their neighbors to make a strong layer, or perhaps even form tight seals to prevent water from passing through the tissue? Junctions serving all of these functions can be found in cells of different types, and here, we’ll look at each of them in turn.

Plasmodesmata

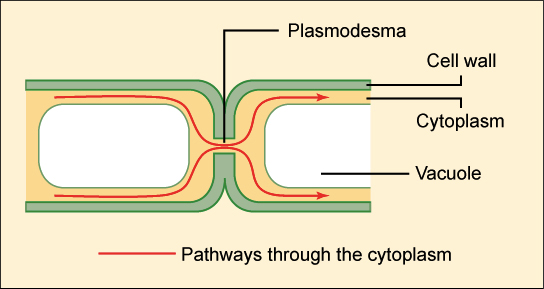

Plant cells, surrounded as they are by cell walls, don’t contact one another through wide stretches of plasma membrane the way animal cells can. However, they do have specialized junctions called plasmodesmata (singular, plasmodesma), places where a hole is punched in the cell wall to allow direct cytoplasmic exchange between two cells.

Image credit: OpenStax Biology.

Plasmodesmata are lined with plasma membrane that is continuous with the membranes of the two cells. Each plasmodesma has a thread of cytoplasm extending through it, containing an even thinner thread of endoplasmic reticulum (not shown in the diagram above).

Molecules below a certain size (the size exclusion limit) move freely through the plasmodesmal channel by passive diffusion. The size exclusion limit varies among plants, and even among cell types within a plant. Plasmodesmata may selectively dilate (expand) to allow the passage of certain large molecules, such as proteins, although this process is poorly understood\[^{1,2}\].

Gap junctions

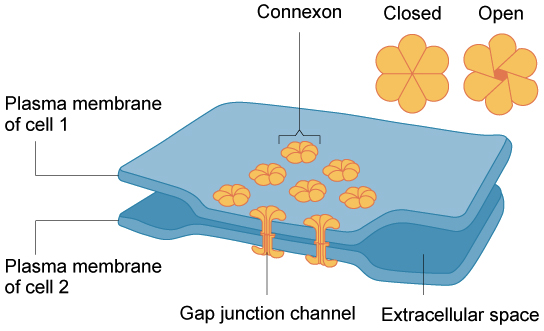

Functionally, gap junctions in animal cells are a lot like plasmodesmata in plant cells: they are channels between neighboring cells that allow for the transport of ions, water, and other substances\[^3\]. Structurally, however, gap junctions and plasmodesmata are quite different.

In vertebrates, gap junctions develop when a set of six membrane proteins called connexins form an elongated, donut-like structure called a connexon. When the pores, or “doughnut holes,” of connexons in adjacent animal cells align, a channel forms between the cells. (Invertebrates also form gap junctions in a similar way, but use a different set of proteins called innexins.)\[^4\]

Image credit: OpenStax Biology. Modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal.

Gap junctions are particularly important in cardiac muscle: the electrical signal to contract spreads rapidly between heart muscle cells as ions pass through gap junctions, allowing the cells to contract in tandem.

Tight junctions

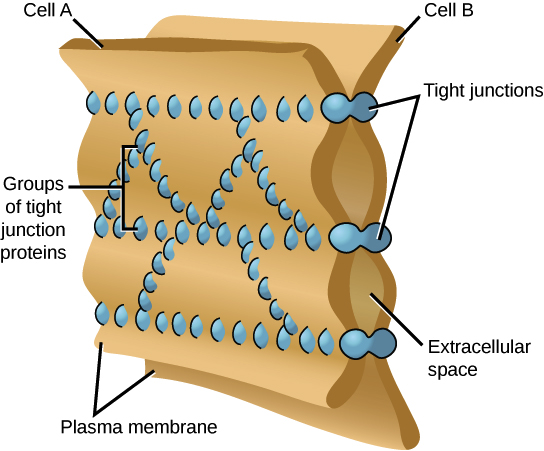

Not all junctions between cells produce cytoplasmic connections. Instead, tight junctions create a watertight seal between two adjacent animal cells.

At the site of a tight junction, cells are held tightly against each other by many individual groups of tight junction proteins called claudins, each of which interacts with a partner group on the opposite cell membrane. The groups are arranged into strands that form a branching network, with larger numbers of strands making for a tighter seal\[^5\].

Image credit: OpenStax Biology. Modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal.

The purpose of tight junctions is to keep liquid from escaping between cells, allowing a layer of cells (for instance, those lining an organ) to act as an impermeable barrier. For example, the tight junctions between the epithelial cells lining your bladder prevent urine from leaking out into the extracellular space.

Desmosomes

Animal cells may also contain junctions called desmosomes, which act like spot welds between adjacent epithelial cells. A desmosome involves a complex of proteins. Some of these proteins extend across the membrane, while others anchor the junction within the cell.

Cadherins, specialized adhesion proteins, are found on the membranes of both cells and interact in the space between them, holding the membranes together. Inside the cell, the cadherins attach to a structure called the cytoplasmic plaque (red in the image at right), which connects to the intermediate filaments and helps anchor the junction.

Desmosomes pin adjacent cells together, ensuring that cells in organs and tissues that stretch, such as skin and cardiac muscle, remain connected in an unbroken sheet.