Conceptual overview of light dependent reactions

Light dependent reactions actors

Photosynthesis: Overview of the light-dependent reactions

Light and photosynthetic pigments

Introduction

If you've ever stayed out too long in the sun and gotten a sunburn, you're probably well aware of the sun's immense energy. Unfortunately, the human body can't make much use of solar energy, aside from producing a little Vitamin D (a vitamin synthesized in the skin in the presence of sunlight).

Plants, on the other hand, are experts at capturing light energy and using it to make sugars through a process called photosynthesis. This process begins with the absorption of light by specialized organic molecules, called pigments, that are found in the chloroplasts of plant cells. Here, we’ll consider light as a form of energy, and we'll also see how pigments – such as the chlorophylls that make plants green – absorb that energy.

What is light energy?

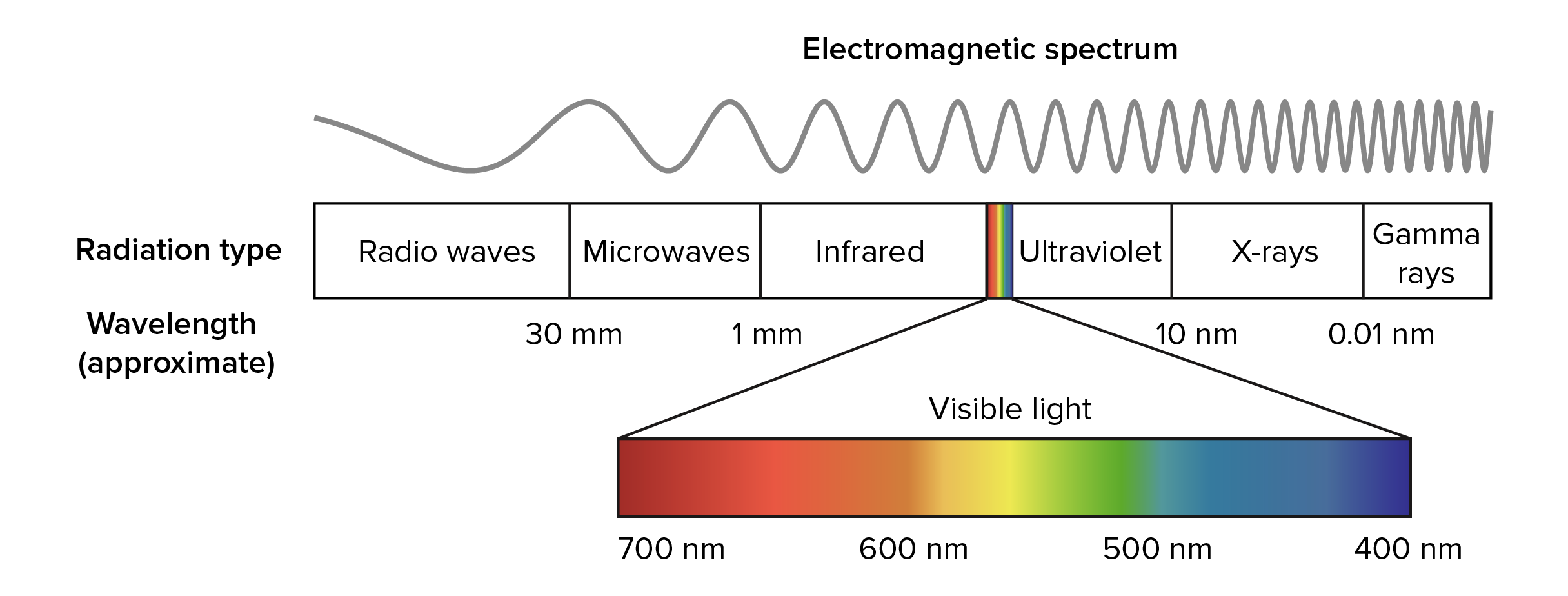

Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation, a type of energy that travels in waves. Other kinds of electromagnetic radiation that we encounter in our daily lives include radio waves, microwaves, and X-rays. Together, all the types of electromagnetic radiation make up the electromagnetic spectrum.

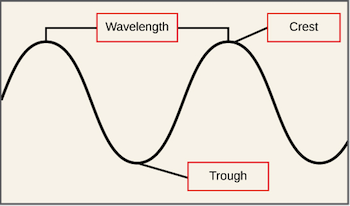

Every electromagnetic wave has a particular wavelength, or distance from one crest to the next, and different types of radiation have different characteristic ranges of wavelengths (as shown in the diagram below). Types of radiation with long wavelengths, such as radio waves, carry less energy than types of radiation with short wavelengths, such as X-rays.

Image modified from "Electromagnetic spectrum," by Inductiveload (CC BY-SA 3.0), and "EM spectrum," by Philip Ronan (CC BY-SA 3.0). The modified image is licensed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

The visible spectrum is the only part of the electromagnetic spectrum that can be seen by the human eye. It includes electromagnetic radiation whose wavelength is between about 400 nm and 700 nm. Visible light from the sun appears white, but it’s actually made up of multiple wavelengths (colors) of light. You can see these different colors when white light passes through a prism: because the different wavelengths of light are bent at different angles as they pass through the prism, they spread out and form what we see as a rainbow. Red light has the longest wavelength and the least energy, while violet light has the shortest wavelength and the most energy.

Although light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation act as waves under many conditions, they can behave as particles under others. Each particle of electromagnetic radiation, called a photon, has certain amount of energy. Types of radiation with short wavelengths have high-energy photons, whereas types of radiation with long wavelengths have low-energy photons.

Pigments absorb light used in photosynthesis

In photosynthesis, the sun’s energy is converted to chemical energy by photosynthetic organisms. However, the various wavelengths in sunlight are not all used equally in photosynthesis. Instead, photosynthetic organisms contain light-absorbing molecules called pigments that absorb only specific wavelengths of visible light, while reflecting others.

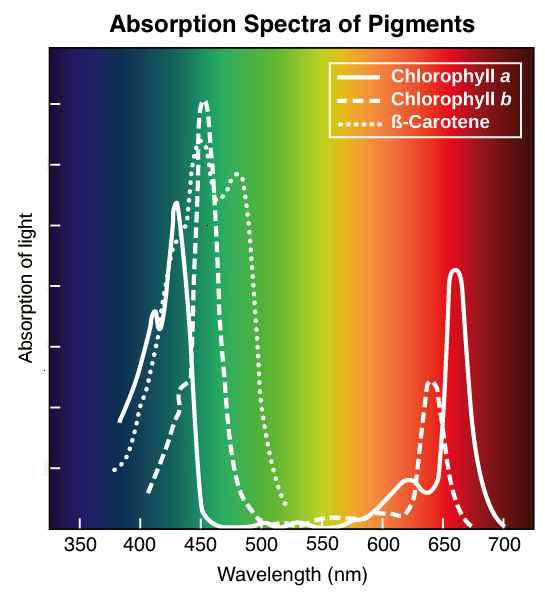

The set of wavelengths absorbed by a pigment is its absorption spectrum. In the diagram below, you can see the absorption spectra of three key pigments in photosynthesis: chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and β-carotene. The set of wavelengths that a pigment doesn't absorb are reflected, and the reflected light is what we see as color. For instance, plants appear green to us because they contain many chlorophyll a and b molecules, which reflect green light.

Optimal absorption of light occurs at different wavelengths for different pigments. Image modified from "The light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis: Figure 4," by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 3.0)

Most photosynthetic organisms have a variety of different pigments, so they can absorb energy from a wide range of wavelengths. Here, we'll look at two groups of pigments that are important in plants: chlorophylls and carotenoids.

Chlorophylls

There are five main types of chlorophylls: chlorophylls a, b, c and d, plus a related molecule found in prokaryotes called bacteriochlorophyll. In plants, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b are the main photosynthetic pigments. Chlorophyll molecules absorb blue and red wavelengths, as shown by the peaks in the absorption spectra above.

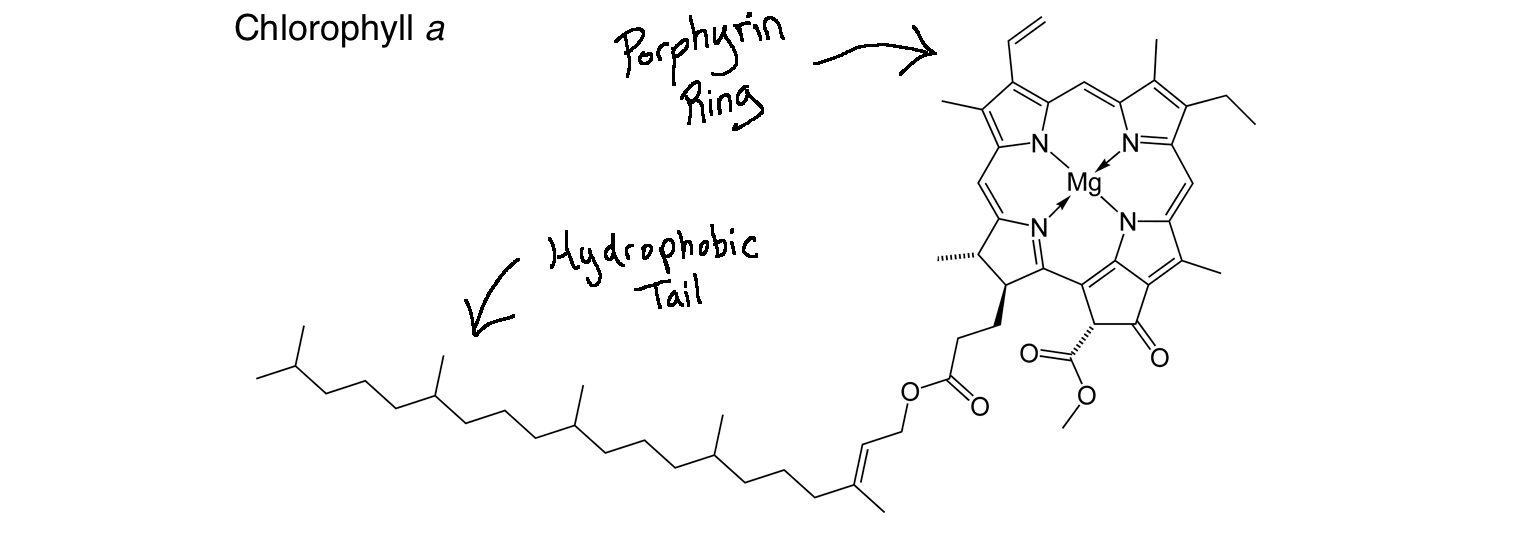

Structurally, chlorophyll molecules include a hydrophobic ("water-fearing") tail that inserts into the thylakoid membrane and a porphyrin ring head (a circular group of atoms surrounding a magnesium ion) that absorbs light\[^1\].

Image modified from "Chlorophyll-a-2D-skeletal," by Ben Mills (public domain)

Although both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b absorb light, chlorophyll a plays a unique and crucial role in converting light energy to chemical energy (as you can explore in the light-dependent reactions article). All photosynthetic plants, algae, and cyanobacteria contain chlorophyll a, whereas only plants and green algae contain chlorophyll b, along with a few types of cyanobacteria\[^{2,3}\].

Because of the central role of chlorophyll a in photosynthesis, all pigments used in addition to chlorophyll a are known as accessory pigments—including other chlorophylls, as well as other classes of pigments like the carotenoids. The use of accessory pigments allows a broader range of wavelengths to be absorbed, and thus, more energy to be captured from sunlight.

Carotenoids

Carotenoids are another key group of pigments that absorb violet and blue-green light (see spectrum graph above). The brightly colored carotenoids found in fruit—such as the red of tomato (lycopene), the yellow of corn seeds (zeaxanthin), or the orange of an orange peel (β-carotene)—are often used as advertisements to attract animals, which can help disperse the plant's seeds.

In photosynthesis, carotenoids help capture light, but they also have an important role in getting rid of excess light energy. When a leaf is exposed to full sun, it receives a huge amount of energy; if that energy is not handled properly, it can damage the photosynthetic machinery. Carotenoids in chloroplasts help absorb the excess energy and dissipate it as heat.

What does it mean for a pigment to absorb light?

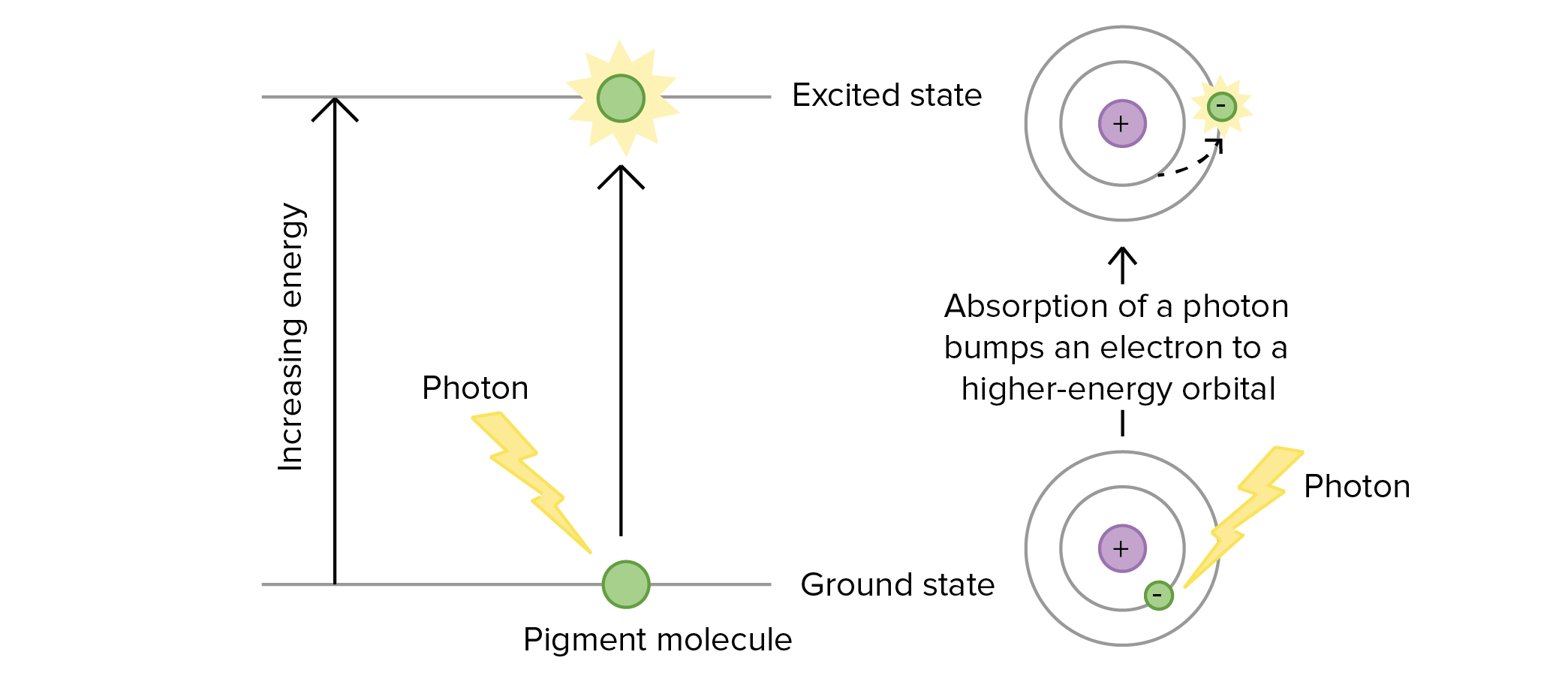

When a pigment absorbs a photon of light, it becomes excited, meaning that it has extra energy and is no longer in its normal, or ground, state. At a subatomic level, excitation is when an electron is bumped into a higher-energy orbital that lies further from the nucleus.

Only a photon with just the right amount of energy to bump an electron between orbitals can excite a pigment. In fact, this is why different pigments absorb different wavelengths of light: the "energy gaps" between the orbitals are different in each pigment, meaning that photons of different wavelengths are needed in each case to provide an energy boost that matches the gap\[^4\].

Image modified from "Bis2A 06.3 Photophosphorylation: the light reactions of photosynthesis: Figures 7 and 8," by Mitch Singer (CC BY 4.0).

An excited pigment is unstable, and it has various "options" available for becoming more stable. For instance, it may transfer either its extra energy or its excited electron to a neighboring molecule. We'll see how both of these processes work in the next section: the light-dependent reactions.

The light-dependent reactions

Introduction

Plants and other photosynthetic organisms are experts at collecting solar energy, thanks to the light-absorbing pigment molecules in their leaves. But what happens to the light energy that is absorbed? We don’t see plant leaves glowing like light bulbs, but we also know that energy can't just disappear (thanks to the First Law of Thermodynamics).

As it turns out, some of the light energy absorbed by pigments in leaves is converted to a different form: chemical energy. Light energy is converted to chemical energy during the first stage of photosynthesis, which involves a series of chemical reactions known as the light-dependent reactions.

In this article, we'll explore the light-dependent reactions as they take place during photosynthesis in plants. We'll trace how light energy is absorbed by pigment molecules, how reaction center pigments pass excited electrons to an electron transport chain, and how the energetically "downhill" flow of electrons leads to synthesis of ATP and NADPH. These molecules store energy for use in the next stage of photosynthesis: the Calvin cycle.

Overview of the light-dependent reactions

Before we get into the details of the light-dependent reactions, let's step back and get an overview of this remarkable energy-transforming process.

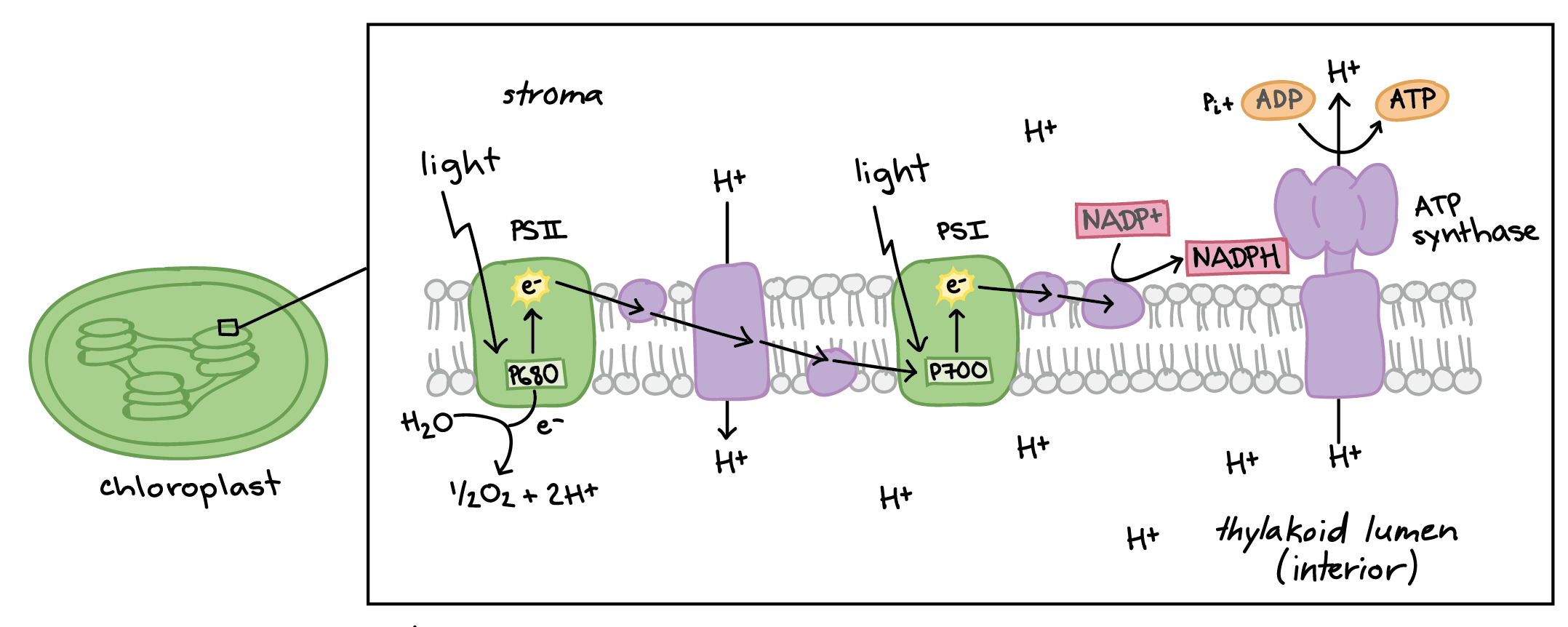

The light-dependent reactions use light energy to make two molecules needed for the next stage of photosynthesis: the energy storage molecule ATP and the reduced electron carrier NADPH. In plants, the light reactions take place in the thylakoid membranes of organelles called chloroplasts.

Photosystems, large complexes of proteins and pigments (light-absorbing molecules) that are optimized to harvest light, play a key role in the light reactions. There are two types of photosystems: photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII).

Both photosystems contain many pigments that help collect light energy, as well as a special pair of chlorophyll molecules found at the core (reaction center) of the photosystem. The special pair of photosystem I is called P700, while the special pair of photosystem II is called P680.

In a process called non-cyclic photophosphorylation (the "standard" form of the light-dependent reactions), electrons are removed from water and passed through PSII and PSI before ending up in NADPH. This process requires light to be absorbed twice, once in each photosystem, and it makes ATP . In fact, it's called photophosphorylation because it involves using light energy (photo) to make ATP from ADP (phosphorylation). Here are the basic steps:

Light absorption in PSII. When light is absorbed by one of the many pigments in photosystem II, energy is passed inward from pigment to pigment until it reaches the reaction center. There, energy is transferred to P680, boosting an electron to a high energy level. The high-energy electron is passed to an acceptor molecule and replaced with an electron from water. This splitting of water releases the \[\text O_2\] we breathe.

ATP synthesis. The high-energy electron travels down an electron transport chain, losing energy as it goes. Some of the released energy drives pumping of \[\text H^+\] ions from the stroma into the thylakoid interior, building a gradient. (\[\text H^+\] ions from the splitting of water also add to the gradient.) As \[\text H^+\] ions flow down their gradient and into the stroma, they pass through ATP synthase, driving ATP production in a process known as chemiosmosis.

Light absorption in PSI. The electron arrives at photosystem I and joins the P700 special pair of chlorophylls in the reaction center. When light energy is absorbed by pigments and passed inward to the reaction center, the electron in P700 is boosted to a very high energy level and transferred to an acceptor molecule. The special pair's missing electron is replaced by a new electron from PSII (arriving via the electron transport chain).

NADPH formation. The high-energy electron travels down a short second leg of the electron transport chain. At the end of the chain, the electron is passed to NADP\[^+\] (along with a second electron from the same pathway) to make NADPH.

The net effect of these steps is to convert light energy into chemical energy in the form of ATP and NADPH. The ATP and NADPH from the light-dependent reactions are used to make sugars in the next stage of photosynthesis, the Calvin cycle. In another form of the light reactions, called cyclic photophosphorylation, electrons follow a different, circular path and only ATP (no NADPH) is produced.

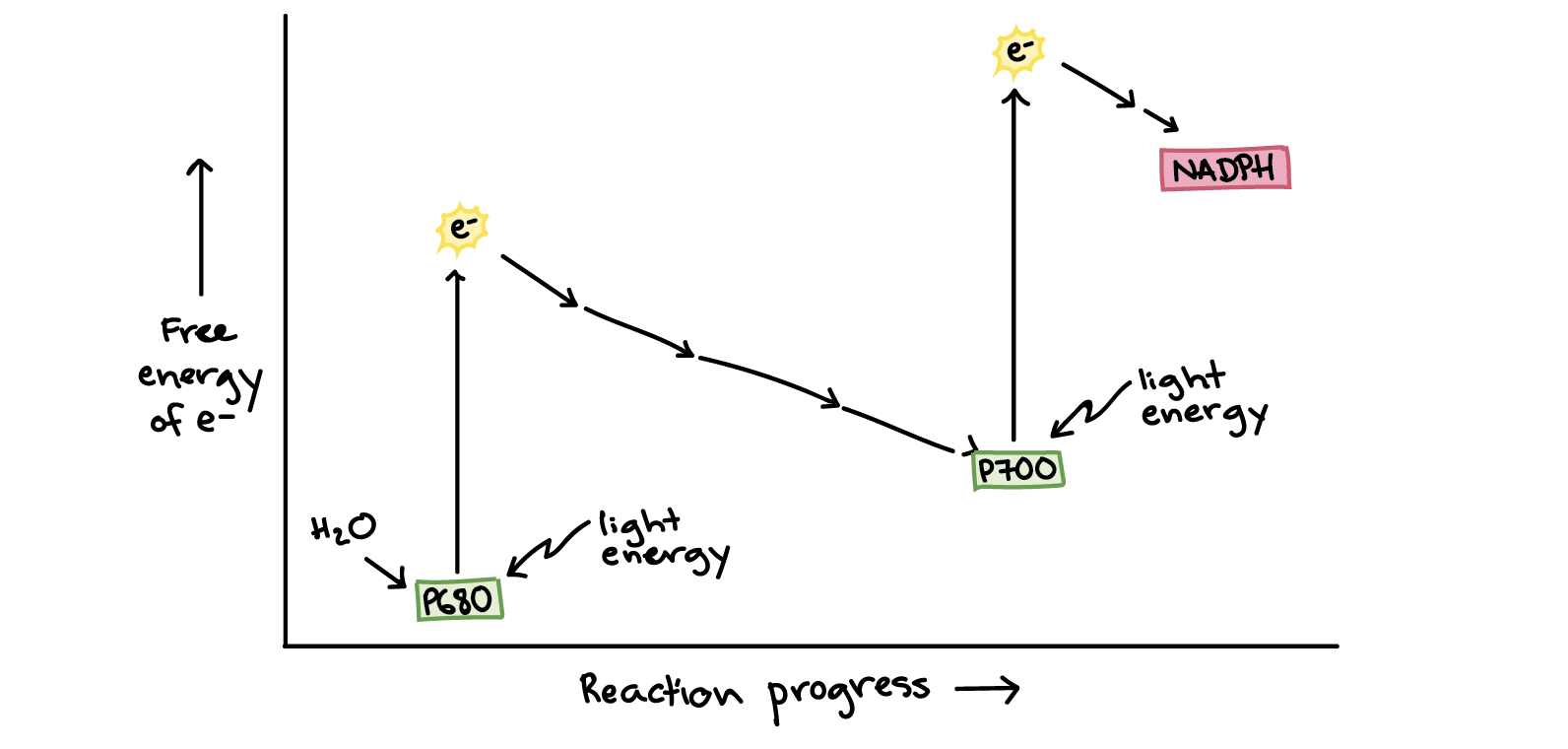

It's important to realize that the electron transfers of the light-dependent reactions are driven by, and indeed made possible by, the absorption of energy from light. In other words, the transfers of electrons from PSII to PSI, and from PSI to NADPH, are only energetically "downhill" (energy-releasing, and thus spontaneous) because electrons in P680 and P700 are boosted to very high energy levels by absorption of energy from light.

Image based on, and partially traced from, similar image by R. Gutierrez\[^5\]

In the rest of this article, we'll look in greater detail at the steps and players involved in the light-dependent reactions.

What is a photosystem?

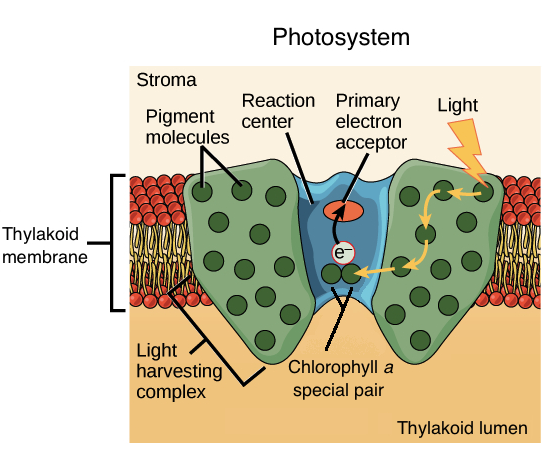

Photosynthetic pigments, such as chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids, are light-harvesting molecules found in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts. As mentioned above, pigments are organized along with proteins into complexes called photosystems. Each photosystem has light-harvesting complexes that contain proteins, \[300\]-\[400\] chlorophylls, and other pigments. When a pigment absorbs a photon, it is raised to an excited state, meaning that one of its electrons is boosted to a higher-energy orbital.

Most of the pigments in a photosystem act as an energy funnel, passing energy inward to a main reaction center. When one of these pigments is excited by light, it transfers energy to a neighboring pigment through direct electromagnetic interactions in a process called resonance energy transfer. The neighbor pigment, in turn, can transfer energy to one of its own neighbors, with the process repeating multiple times. In these transfers, the receiving molecule cannot require more energy for excitation than the donor, but may require less energy (i.e., may absorb light of a longer wavelength)\[^6\].

Collectively, the pigment molecules collect energy and transfer it towards a central part of the photosystem called the reaction center.

Image modified from "The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis: Figure 7," by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 4.0.

The reaction center of a photosystem contains a unique pair of chlorophyll a molecules, often called special pair (actual scientific name—that's how special it is!). Once energy reaches the special pair, it will no longer be passed on to other pigments through resonance energy transfer. Instead, the special pair can actually lose an electron when excited, passing it to another molecule in the complex called the primary electron acceptor. With this transfer, the electron will begin its journey through an electron transport chain.

Photosystem I vs. photosystem II

There are two types of photosystems in the light-dependent reactions, photosystem II (PSII) and photosystem I (PSI). PSII comes first in the path of electron flow, but it is named as second because it was discovered after PSI. (Thank you, historical order of discovery, for yet another confusing name!)

Here are some of the key differences between the photosystems:

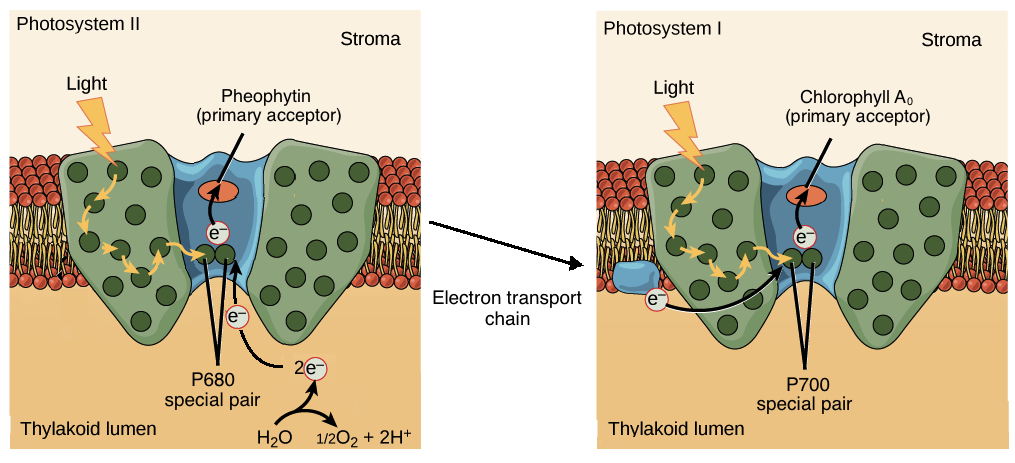

Special pairs. The chlorophyll a special pairs of the two photosystems absorb different wavelengths of light. The PSII special pair absorbs best at 680 nm, while the PSI special absorbs best at 700 nm. Because of this, the special pairs are called P680 and P700, respectively.

Primary acceptor. The special pair of each photosystem passes electrons to a different primary acceptor. The primary electron acceptor of PSII is pheophytin, an organic molecule that resembles chlorophyll, while the primary electron acceptor of PSI is a chlorophyll called \[\text A_0\]\[^{7,8}\].

Source of electrons. Once an electron is lost, each photosystem is replenished by electrons from a different source. The PSII reaction center gets electrons from water, while the PSI reaction center is replenished by electrons that flow down an electron transport chain from PSII.

Image modified from "The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis: Figure 7," by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 4.0.

During the light-dependent reactions, an electron that's excited in PSII is passed down an electron transport chain to PSI (losing energy along the way). In PSI, the electron is excited again and passed down the second leg of the electron transport chain to a final electron acceptor. Let’s trace the path of electrons in more detail, starting when they're excited by light energy in PSII.

Photosystem II

When the P680 special pair of photosystem II absorbs energy, it enters an excited (high-energy) state. Excited P680 is a good electron donor and can transfer its excited electron to the primary electron acceptor, pheophytin. The electron will be passed on through the first leg of the photosynthetic electron transport chain in a series of redox, or electron transfer, reactions.

After the special pair gives up its electron, it has a positive charge and needs a new electron. This electron is provided through the splitting of water molecules, a process carried out by a portion of PSII called the manganese center\[^9\]. The positively charged P680 can pull electrons off of water (which doesn't give them up easily) because it's extremely "electron-hungry."

When the manganese center splits water molecules, it binds two at once, extracting four electrons, releasing four \[\text H^+\] ions, and producing a molecule of \[\text O_2\].\[^{9}\] About \[10\] percent of the oxygen is used by mitochondria in the leaf to support oxidative phosphorylation. The remainder escapes to the atmosphere where it is used by aerobic organisms (such as us!) to support respiration.

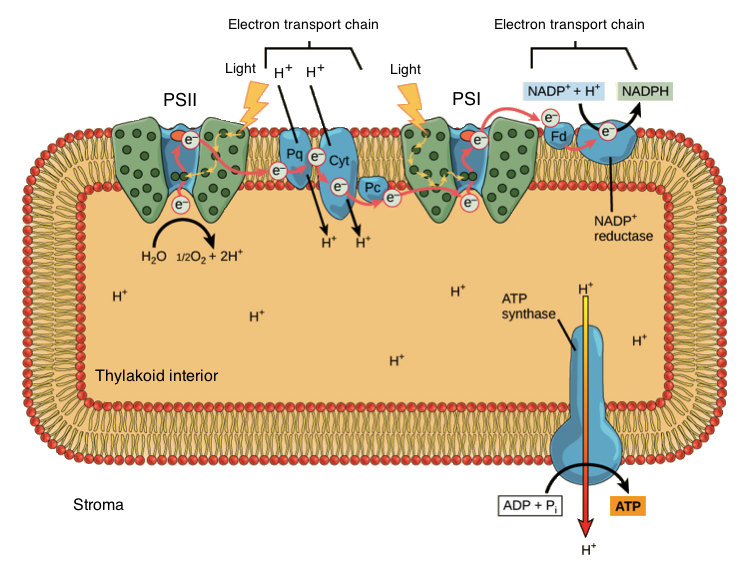

Electron transport chains and photosystem I

When an electron leaves PSII, it is transferred first to a small organic molecule (plastoquinone, Pq), then to a cytochrome complex (Cyt), and finally to a copper-containing protein called plastocyanin (Pc). As the electron moves through this electron transport chain, it goes from a higher to a lower energy level, releasing energy. Some of the energy is used to pump protons (\[\text H^+\]) from the stroma (outside of the thylakoid) into the thylakoid interior.

This transfer of \[\text H^+\], along with the release of \[\text H^+\] from the splitting of water, forms a proton gradient that will be used to make ATP (as we'll see shortly).

Image modified from "The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis: Figure 8," by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 4.0.

Once an electron has gone down the first leg of the electron transport chain, it arrives at PSI, where it joins the chlorophyll a special pair called P700. Because electrons have lost energy prior to their arrival at PSI, they must be re-energized through absorption of another photon.

Excited P700 is a very good electron donor, and it sends its electron down a short electron transport chain. In this series of reactions, the electron is first passed to a protein called ferredoxin (Fd), then transferred to an enzyme called NADP\[^+\]reductase. NADP\[^+\] reductase transfers electrons to the electron carrier NADP\[^+\] to make NADPH. NADPH will travel to the Calvin cycle, where its electrons are used to build sugars from carbon dioxide.

The other ingredient needed by the Calvin cycle is ATP, and this too is provided by the light reactions. As we saw above, \[\text H^+\] ions build inside the thylakoid interior and make a concentration gradient. Protons "want" to diffuse back down the gradient and into the stroma, and their only route of passage is through the enzyme ATP synthase. ATP synthase harnesses the flow of protons to make ATP from ADP and phosphate (\[\text P_i\]). This process of making ATP using energy stored in a chemical gradient is called chemiosmosis.

Some electrons flow cyclically

The pathway above is sometimes called linear photophosphorylation. That's because electrons travel in a line from water through PSII and PSI to NADPH. (Photophosphorylation = light-driven synthesis of ATP.)

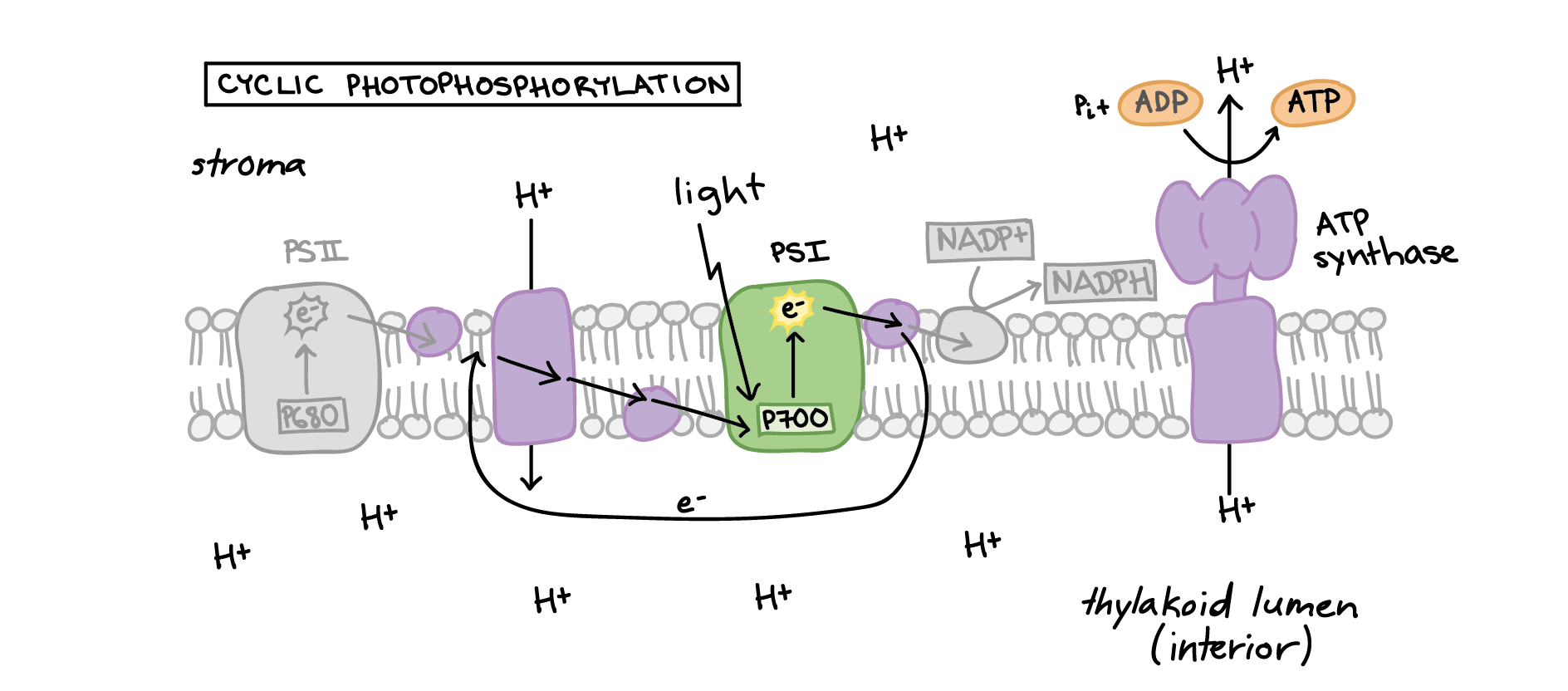

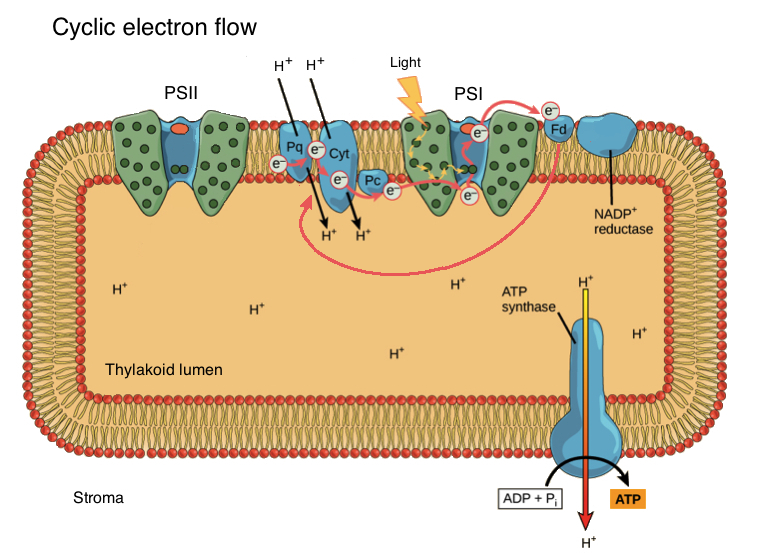

In some cases, electrons break this pattern and instead loop back to the first part of the electron transport chain, repeatedly cycling through PSI instead of ending up in NADPH. This is called cyclic photophosphorylation.

After leaving PSI, cyclically flowing electrons travel back to the cytochrome complex (Cyt) or plastoquinone (Pq) in the first leg of the electron transport chain\[^{10,11}\]. The electrons then flow down the chain to PSI as usual, driving proton pumping and the production of ATP. The cyclic pathway does not make NADPH, since electrons are routed away from NADP\[^+\] reductase.

Image modified from "The Light-Dependent Reactions of Photosynthesis: Figure 8," by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 4.0.

Why does the cyclic pathway exist? At least in some cases, chloroplasts seem to switch from linear to cyclic electron flow when the ratio of NADPH to NADP\[^+\] is too high (when too little NADP\[^+\] is available to accept electrons)\[^{12}\]. In addition, cyclic electron flow may be common in photosynthetic cell types with especially high ATP needs (such as the sugar-synthesizing bundle-sheath cells of plants that carry out \[\text C_4\] photosynthesis)\[^{13}\]. Finally, cyclic electron flow may play a photoprotective role, preventing excess light from damaging photosystem proteins and promoting repair of light-induced damage\[^{14}\].